Room III.

FAR AWAY

Articles made by Oriental cultures have always seemed enigmatic, alluring, mysterious and exotic to Europeans. They have often been imitated as well. This imitation of the materials, forms and decoration typical of the Orient gave rise to the trend known as Chinoiserie. Despite its etymology, Chinoiserie also embraces aspects deriving from Japan, India and the Middle East.

Porcelain itself was an enigmatic, unknown material in Europe until 1708, when European true or hard-paste porcelain was discovered by two German arcanists, Johann Friedrich Böttger and Ehrenfried Walther von Tschirnhausen. Until then, the special translucent material had been imitated. Faience, for instance, was painted with cobalt-blue Chinese ornamentation on a white lead glaze.

The early porcelain painting of the 18th century drew heavily on Chinese ornamentation and that of Japanese Arita or Imari porcelains, where the decoration was done in underglaze cobalt blue and overglaze red and gold. The Chinoiserie of the 18th century culminated in the Rococo style, which marked a break from the Oriental prototypes.

Herend Chinoiserie is unique for the many, varied ways in which Mór Fischer reworked and reproduced the styles of Far Eastern porcelain. Fischer was no scholar or connoisseur of Oriental iconography. He too was taken by the exotic, varied forms and ornamentation of the objects he encountered.

Fischer often selected freely from a range of Oriental styles, with an eclectic approach typical of his age. Often, Herend Chinoiserie pieces are not true copies or replicas, but original works. In technical matters, however, Fischer was keen to reproduce the authentic beauty of Oriental porcelain.

The variety of raw materials resulted from deliberate experimentation-respect for the original and a desire to recreate it perfectly-not technical imperfection.

When applying Fischer's decoration to Herend Chinoiserie porcelain, painters would draw the outlines and then fill the areas with colour, before outlining them again. This makes the thick overglaze paints protrude from the surface. Chinese painters, on the other hand, paint the ornamentation smoothly and continuously with the brush, so that it stays closer to the glazed surface.

The pieces displayed in the room can be classed by their decoration. The patterns represented are Ming, Poissons, Siang rouge (Gödöllő), Siang jaune, Siang noire, Cubash, Paon de Péking, Esterházy, Empereur, Macao, and Kyoto They are grouped by pattern, not age. This makes it possible to see how the painting methods and materials changed over about 80 years.

Among the exhibits is an 18th-century Japanese Imari plate, conspicuous also for its size. This has belonged to the Budapest Museum of Applied Arts since 1952, but it was not displayed before because of its poor condition. It has now been restored for this exhibition. It may have belonged originally to an aristocratic collection, before suffering damage and being passed to Mór Fischer for his experiments.

A typical experiment of Fischer's is the strongly coloured plate in an eclectic style, the well of it covered in thick body colour and enamel paints, showing a scene resembling Japanese lacquer work, framed like a scroll.

The collection of Fischer's pieces also reflects the fragmentation of the Hungarian aristocratic collections wrought by two world wars and other vicissitudes. However, the pieces demonstrate the enthusiasm and the wealth of the art - loving collectors - aristocrats and commoners - who patronized Herend in the second half of the 19th century.

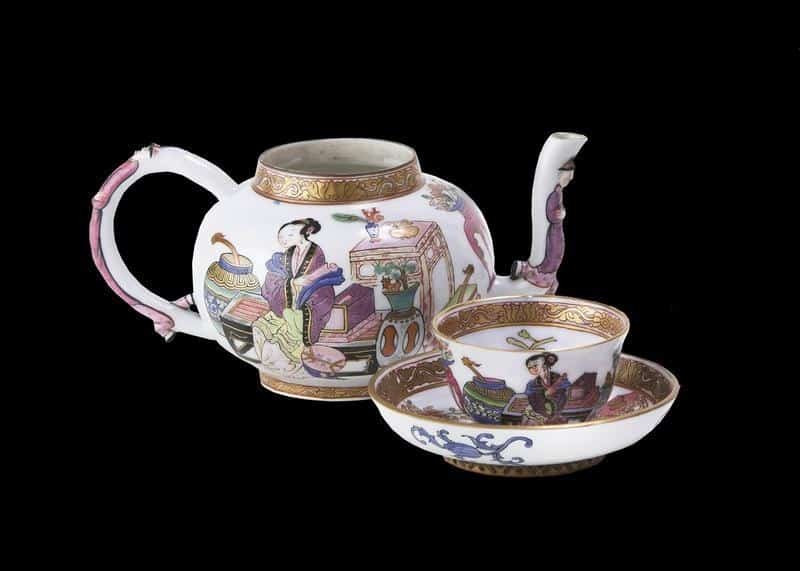

CUP AND SAUCER DECORATED WITH ESTERHÁZY PATTERN

Fischer's porcelain was also popular among the wealthier middle classes, but the biggest orders came from the aristocracy. The finest décors were named after the first person to order them or after a family to which Fischer presented a prized pattern.

Miklós Esterházy, ambassador in St Petersburg, had brought back to Hungary the prototype of the Esterházy décor. The ground of brick red or green is scraped away with a paintbrush handle to produce the stylized sedge motifs, beside which tiny Chinese characters are painted.

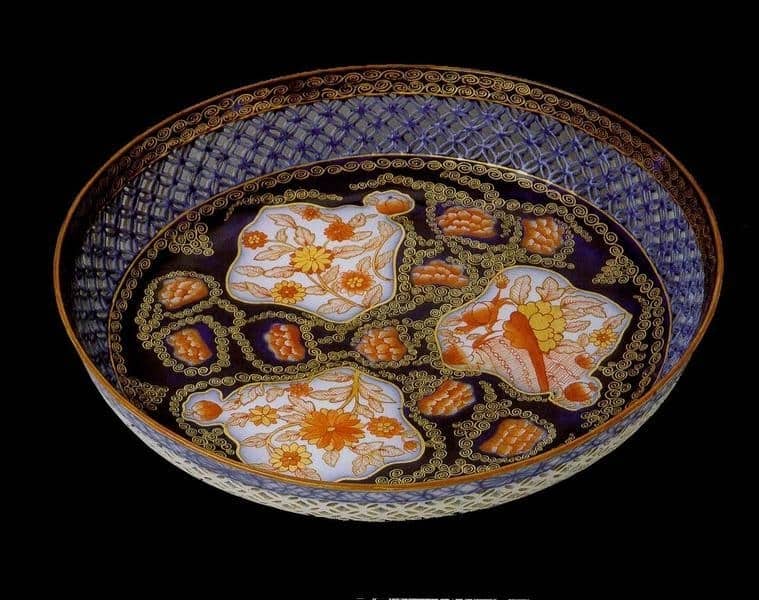

IMARI DISH

The 18th-century Imari ornamental plate displayed probably belonged to an aristocratic family before it was damaged and passed to Mór Fischer. Owned by the Budapest Museum of Applied Arts since 1952, it has now been carefully restored. During the restoration work, it was discovered that Fischer had experimented with the plate, by painting over the original decoration.

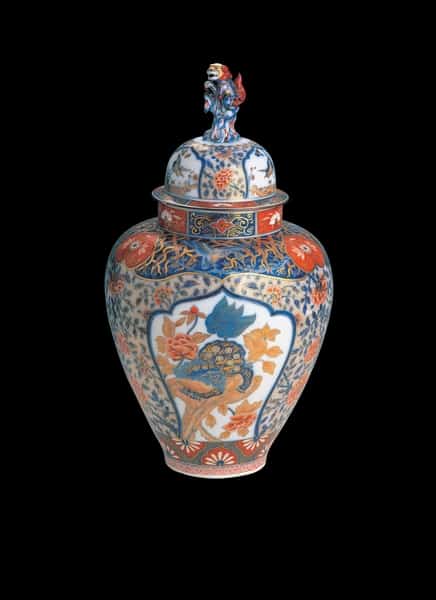

IMARI VASE

The well-known Japanese porcelain style known as Imari developed in the 17th century after the discovery of the Arita kaolin deposits. This name, current in Europe, comes from the nearby port from which sizeable quantities of the ware were shipped by Dutch traders. Imari porcelain had a strong influence on the porcelain patterns developed after true porcelain began to be made in Europe in 1709. Initially, Imari porcelain was decorated with underglaze blue. Later red, green, yellow and black were also used. The pieces show Chinese influence as well, in the shape and decoration.

OBJECTS DECORATED WITH MING PATTERN

The period of the Chinese Ming dynasty (1368-1644) brought the golden age of porcelain. The shapes of the blueish-green porcelain pieces are very varied, with colourful decoration (landscapes or reclining figures). This type of Chinese porcelain reached Europe through Dutch traders and inspired European faience and later porcelain factories to make Chinese-style objects. Chinoiserie décors were made also at Herend in the 1850s, among them the Ming pattern, showing a seated woman in a Chinese interior, painted in enamel, surrounded by a gilded garland. A mid-19th-century king of Sardinia had an incomplete service in this pattern, for which no European factory had been willing to provide replacers. The ambassador of the kingdom turned to Mór Fischer, who undertook the task. Fischer delivered the pieces personally to the Turin court, where he managed to exchange the ones he had made for originals. The lords expressed reservations about these compared with the 'originals' Then Fischer revealed the truth and the Herend pieces greatly enhanced the manufactory's reputation.